A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE EXOTIC SHORTHAIR

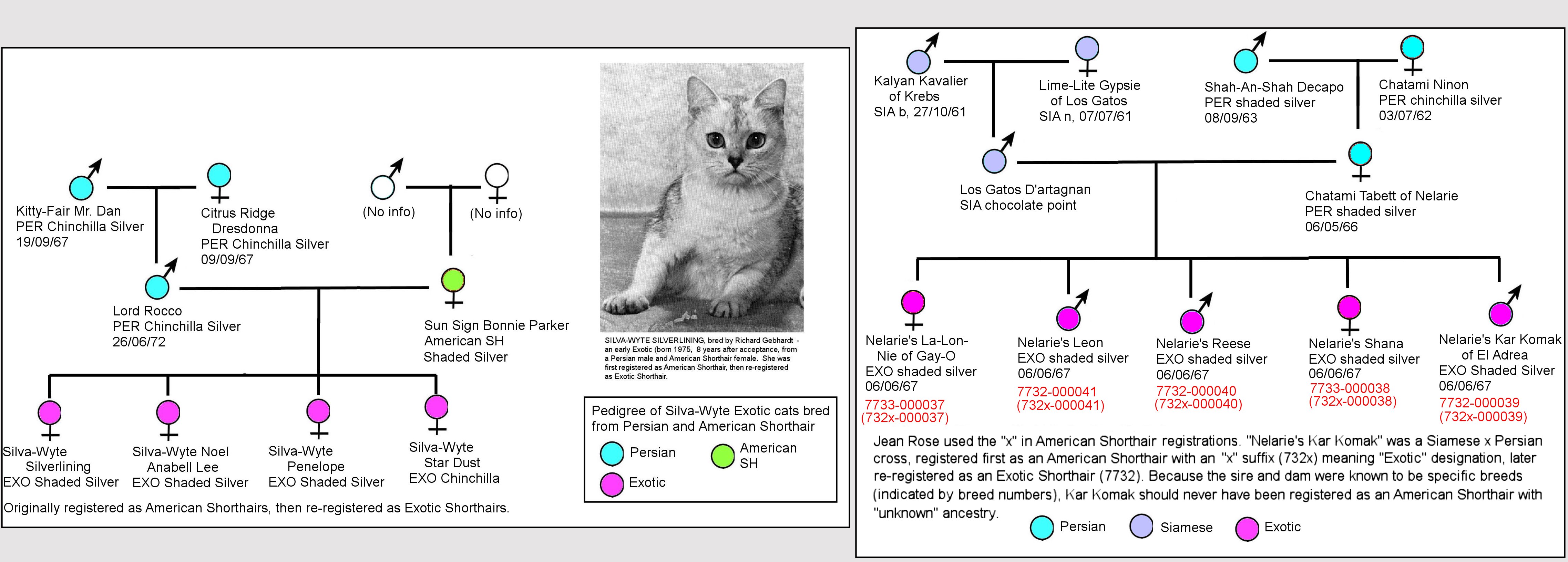

Although not strictly permitted by American cat registries, in the late 1950s and early 1960’s some American Shorthair breeders introduced new colours into the American Shorthair using Persians, British Shorthairs and Russian Blues. In a similarly controversial breeding practice, Burmese were crossed with American Shorthairs, resulting in a cat distinctly different from the "common" American Shorthair. These crosses could be registered as American Shorthair foundation cats.

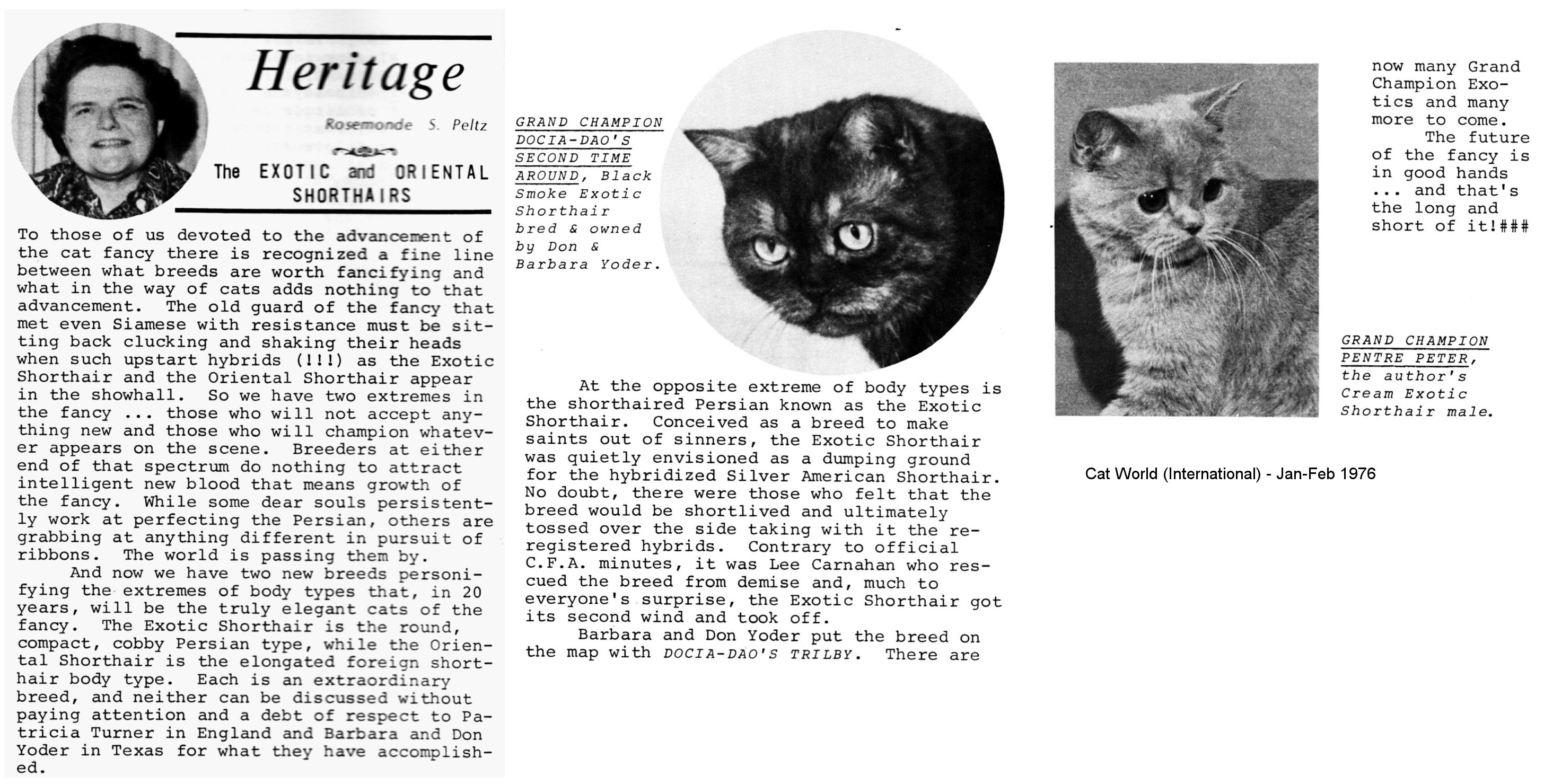

To eliminate tabby markings in the Shaded Silver American Shorthair, other breeds were added. Wayne Park used a chocolate point Siamese to introduce the agouti (ticked) tabby pattern gene to get rid of the excessive leg barring and clear up the coat. This meant that pointed cats and chocolate-silvers occurred, and the shaded silver American Shorthairs were often more "refined" in type. Other breeders use Burmese to introduce the ticked tabby pattern, but this apparently gave the red colours a "muddy" appearance. Some breeders used Abyssinians to get the ticked tabby gene, but this adversely affected ear conformation and colour distribution. The use of Chinchilla Persians meant that later breeders had to decide whether their cats would be American Shorthairs or become Exotic Shorthairs ("… the shorthaired Persian known as the Exotic Shorthair was conceived to make saints out of sinners. The Exotic Shorthair was quietly envisioned as a dumping ground for the hybridized Silver American Shorthair. No doubt there were those who felt that the breed would be short-lived and ultimately tossed over the side taking with it the registered hybrids." Rosemonde Peltz, Cat World [USA], Jan-Feb 1976)

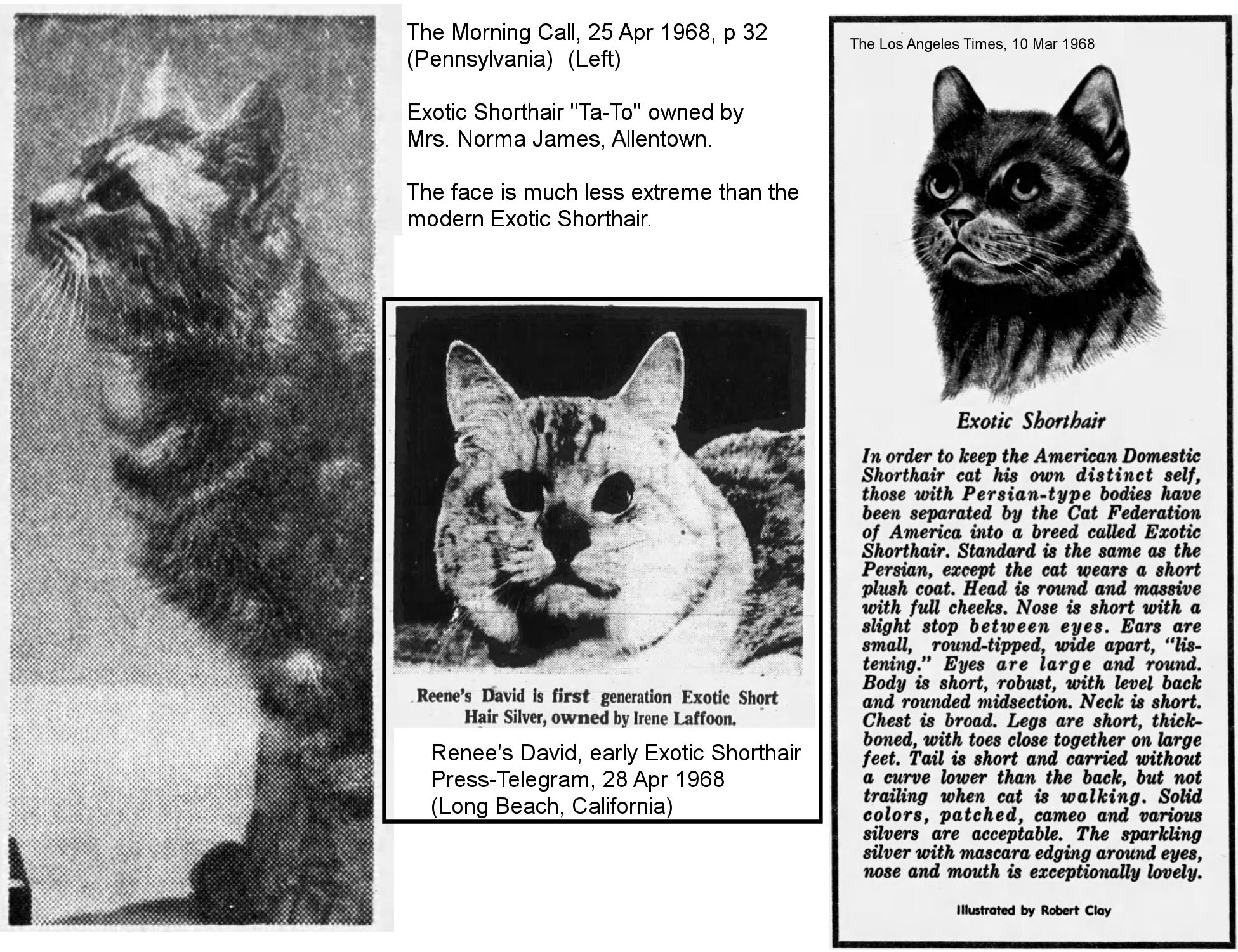

Since the late 19th century, British breeders had crossed British Shorthairs with Persians. On the one hand this added new colours to the Persian. On the other hand it "improved" the British Shorthair into a cobby, thick-furred cat than, moving it away from its common-or-garden shorthair forebears. These crosses also produced kittens that were too "Persian" in type, or whose coat was too long and soft for the British Shorthair standard. Some breeders found the appearance attractive in its own right. Australian breeders became aware of the American Exotic Shorthair and began their own breeding programme using Persians, domestic shorthairs, British Shorthairs and Scottish Folds. Despite the different foundation cats used in different countries, the end result was a shorthaired version of the Persian. In September 1966, the CFA created a hybrid class for Domestic Shorthairs of mixed Persian and American Shorthair parentage. The standard was based on the Persian standard. In a CFA report from 1967, in view of evidence indicating that British breeders had used Persians with their British Shorthairs, the CFA National Breed Council recommended that from then on all imported British Shorthairs should be registered as Exotic Shorthairs. This recommendation was accepted.

In the 1967 CFA report, Mrs. Sample pointed out that she, Mrs. Rose and Mr. Winn had pursued the problem of handling hybrids (meaning cross-breeds, not wild hybrids). Mrs. Rose explained that silver was not a natural colour in the American Shorthair and that many, if not all, of those registered had Persian ancestry. Mrs. Martinke stated some of these silver shorthairs had Persian grandparents but met the American Shorthair standard so they were registered (disingenuously) "Parentage unknown." They resembled a Silver Persian just after clipping. Mrs. Rose felt the solution to this might be the separation of the true American Shorthairs and establishment of another class of shorthairs known as Exotic Shorthairs. The American Shorthair standard would remain unchanged.

It was important to set up a programme immediately for the registration of "Hybrids." Mrs. Rose stated that many of the registrations handled by the CFA Central Office went directly to the girls who did the filing of registrations and she never saw them. This was because it was important to process registrations quickly. Several things could be done to remedy the situation in American Shorthairs, where cats had been registered for years as "Parentage unknown" and it was very probable that long hairs were in the background of some of those cats. Three possibilities were suggested.

The first was to create a new class for Chinchilla and Shaded Silver Shorthairs and call them "Sterling" silvers. Cats with longhair parentage were allowable. The second was to create an "Exotic Shorthair" Hybrid class for Domestic Shorthairs with mixed Persian and American Shorthair parentage. The third was to leave all American Shorthairs where they were at that time and to do away with PR registrations, which would also allow first generation Himalayans and Red Colourpoints to be registered.

Mrs. Rose stated that the Central Office would code Exotic Shorthair cats by adding the letter "x" to their registration number. Mrs. Bloem’s motion that a new standard based on the Persian Standard for type be established for Exotic Shorthairs was accepted. The Exotic Shorthairs would be given championship classification; their standard would be entirely different from the American Shorthair Standard and would be closer to the Persian standard, excepting fur length. American Shorthair breeders could register their kittens either as American Shorthairs or as Exotic Shorthairs, depending on ancestry. Once registered as Exotics they, and their progeny, could not revert to being American Shorthairs.

The Exotic Shorthair was recognised in the USA in the late 1960s and in Britain and Continental Europe in 1986. They could be outcrossed to Persians to maintain the conformation and the initial standard was identical to that of the Persian, except for coat length. The standard removed the description of the nose break, in order to prevent some of the health issues appearing in the extreme flat-faced Persians, but continued crossing to Persians meant the face shape of the Exotic Shorthair became identical, nose-break and all! The nose break was added into the standard. Exotic Shorthair enthusiasts sometimes referred to the breed as "Persians in Petticoats" because they were like Persians in every way except for the short fur. This made them ideal for those who loved the Persian look, but did not have the time to groom a Persian each day - it was "the lazy man's Persian."

In the USA, Bob and Nancy Lane founded the Exotic Shorthair Fanciers in 1969 to encourage the breed. According to the San Francisco Examiner (12th October 1985) Don Swanson stated that within five years the Exotic Shorthair would become the most popular breed of cat in the United States.

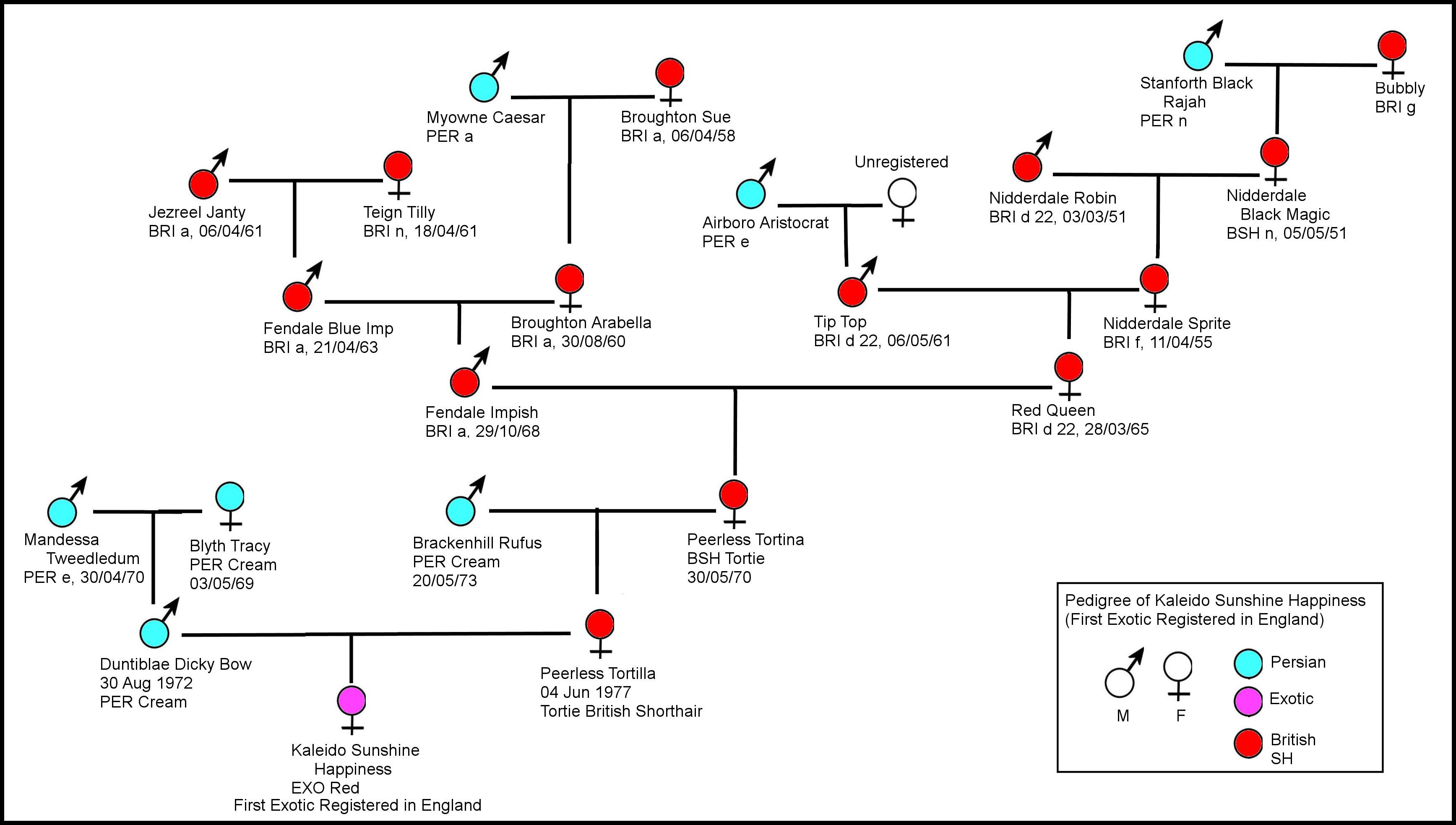

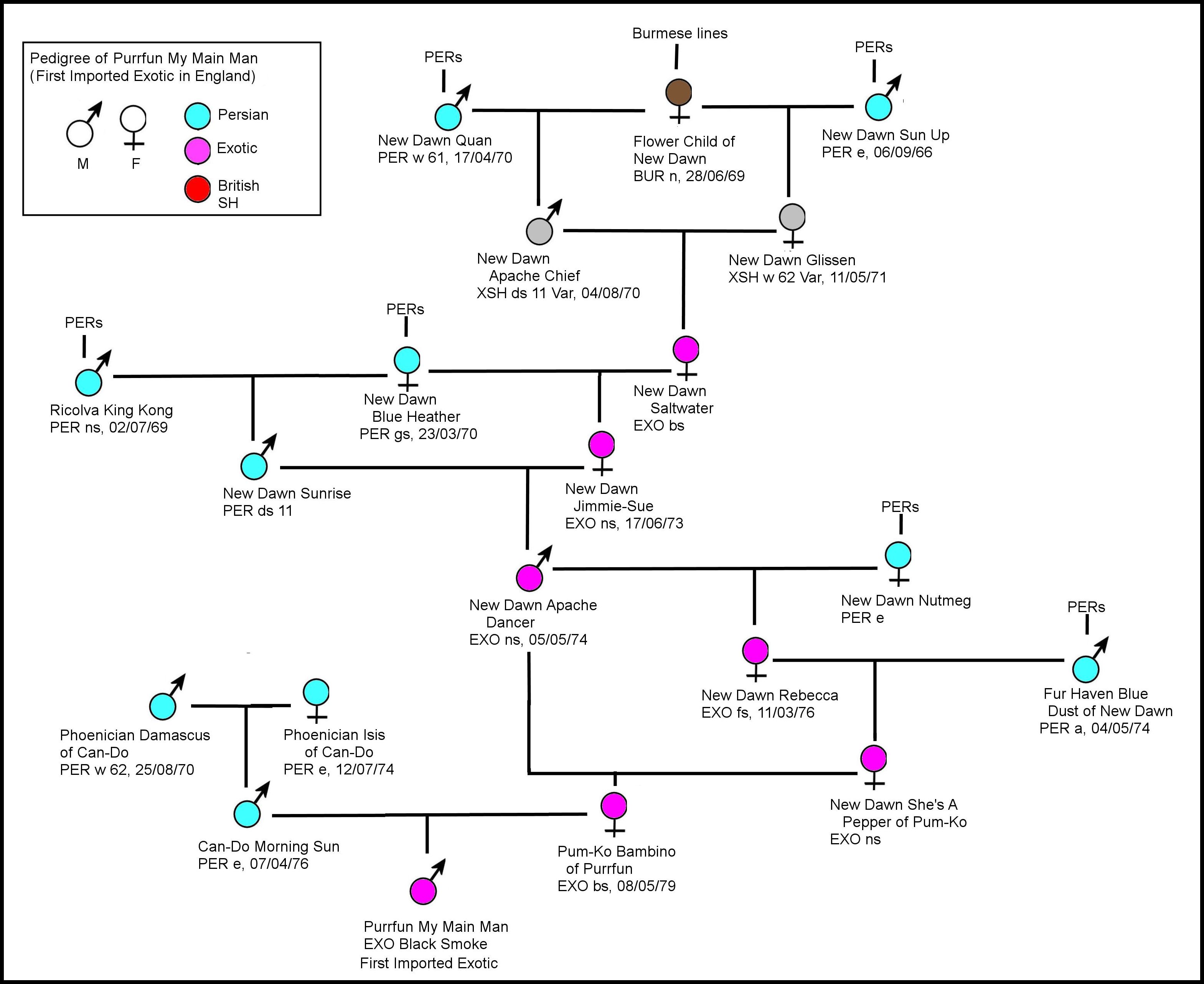

The first Exotic Registered in England was a red called Kaleido Sunshine Happiness bred from Persians and British Shorthairs in the late 1970s. The first Amerian Exotic Shorthair imported to the UK was CFA Gr Ch Purrfun My Main Man, a Black Smoke born in 1980. It was discovered that his mother was a chocolate smoke - a colour the GCCF didn’t recognise at the time - so his registration was withdrawn. He had Burmese several generations back on his mother’s side. The BUR x PER crossings produced Experimental Shorthair (XSH) half-siblings that were bred to each other and the XSH x XSH son, New Dawn Saltwater, a brown smoke, was registered as an Exotic Shorthair. Exotics were formally recognised by the GCCF in 1986, and gained Championship status in 1995.

In Cat World (International) March-April 1978, Rosemonde S. Peltz revisited the Exotic Shorthair. "Several months ago, some readers of this column took me to task when I stated that there is periodic hybridization between Persians and British Shorthairs. No one doubted the sincerity of such criticism although I was astounded by their naivete. Most American breeders do believe such hybridization ended shortly after World War II. Perhaps they will be interested in the following paragraphs from the January 12, 1978, issue of Fur & Feather, page 34:

"Listening to visitors' comments on British Shorthair exhibits I heard it said repeatedly: ‘What's special about THAT cat?' Certainly some of today's British Shorthairs lack the great muscular magnificence of Some of our older cats such as Mrs. Nash's Grand Premier Jezreel Martyn and Mrs. Procter's Champion Broadweir Someone Special. Realising this, Mrs. Marjorie Bishop, famed for her Lecreme Longhairs, mated her Blue Persian queen Champion Peela Genevieve to Mrs. Watling's British Blue, Champion Shadingfield Hercules, and one of their kittens, Mocha Sister Jill, a magnificent British Blue female, was first in a class of fifteen kittens at the National this year. Such outcrosses MUST be of benefit to a breed and we are fortunate that such crosses are not penalised in this country as they are in some overseas countries." The writer continues that she does not advocate indiscriminate mixing of breeds but "some planned scientific outcrosses are occasionally necessary."

To put all of this in proper perspective it should be noted that CFA placed all such hybrid cats, both American and British, into the breed class: Exotic Shorthairs. It was felt by some that the different conformation was attributable to the differences between the American and English longhairs. And, of course, there are also differences between American and British Shorthairs. Recently, CFA advanced British Shorthairs to Provisional status. This was done because of assurances that sufficient numbers of cats had been imported to provide pure breeding stock. There is nothing scientific about hybridization when it is done every 3rd or 4th generation just to improve the appearance of the cat. Because of the quarantine regulations, Britain is a "tight little island" and, consequently, registered breeding stock can be limited. There is no penalty in the United States for hybridization. We have several breeds of cats maintained by hybridization. However, we do feel that a pedigree is something of value and the purchaser of a cat should be given all the facts."

In her "Heritage" Column she expanded on the Exotic Shorthair:

"Probably for as long as anyone can remember, longhaired cats mated with short coated ones and we have all seen the products in our neighbours' cats. ‘Fluffy' and all of her semi-longhaired cousins are seen throughout the world. The idea of purposefully crossing purebred Persians and short coated cats came about in rather a unique fashion. Exotic Shorthairs were established as a breed in order to cull out from the central registry those cats of mixed ancestry. Whether or not the records ever got straight is no longer of great concern to those breeders who have developed the Exotic Shorthair. A solid, chunky cat, rounded in all directions, constituted the frame upon which the short coat is hung. The cat was a short coated Persian except, at the beginning, a nose break was not allowed. That was quickly changed since a Persian was not a Persian without a nose break deep enough for judges to put a knuckle in. Fortunately, Exotic Shorthair breeders have been intelligent enough to avoid the typical ‘peking' of today's Persian and most are of the firm conviction that nostrils should not be located between the eyes.

The next step that altered the original concept was that of narrowing down the breeds of shorthairs that could be used to make an Exotic. Initially, several of the better cats were of Persian-Burmese parentage. However, the problem of future intermediate coated brown cats was foreseen. In spite of our supreme obeisance to type, color does indeed count and there was no great desire to incorporate the brown coat into the breed. In addition, breeders felt that most of the short coated breeds, with the exception of the American Shorthair, had little to offer to future generations of Exotic Shorthairs. So here was an interesting twist that returned us to the original scene of the crime. Having been designed to rid the American Shorthair breed of the previously highly desirable soft, flyaway coated Silvers, the Exotic was now limited to use of American Shorthairs, Exotics and Persians as stock for breeding.

Another event in the history of the breed was the forced registration of British Shorthairs as Exotics in CFA. Here was another source of hybridized longhair-shorthair stock. Such cats produced a better coat in a shorter period of time. The problem that needs breeders' attention is the coat. Although the term "short coated Persian" is often used the Exotic does not have a short coat. It is intermediate in length and it is balanced. The length appears to confuse some. An evennness of coat is essential. There should be no suggestion of feathers either on extremities, ears of tail. The texture is soft. It is a dense, thick coat that results from an elimination of overhanging guard hairs. If the quality of coat and type is to be maintained and hopefully improved, then the breeder would do well to be quite rigid in selection of stock. The winning Persian or the winning American Shorthair is not always the best parent for an Exotic Shorthair.

The American Shorthair, if judged correctly to Standard, has a hard coat. Such a coat will not help the Exotic. There is a tendency for some very pretty and winning Persians to be too small of head and bone. They will do little to benefit the Exotic. Let us not produce delicate, hot-house flowers. The Exotic needs a massive head with small ears and large expressive eyes. His nose is for breathing, not running. His eyes are to see with, not to tear. We should strive to produce cats that are aesthetically pleasing, strong and healthy."

According to The UK’s GCCF (Exotic Breeding Policy, by the Exotic Breed Advisory Council, September 2010-April 2011 "The history of the Exotic breed is well documented. For many years, British Shorthair breeders had occasionally mated their British cats to Longhairs in order to improve the bone, body shape, eye colour etc [of the British Shorthair]. The subsequent kittens from these matings were usually too 'over-typed' or with an overly soft and long coat to show them as British Shorthairs. They were nevertheless very attractive with a look of their own, having the characteristics of the Persian but with a short plush coat. Some breeders were keen to maintain this different 'look' and decided to develop a 'new' breed by breeding from these kittens (mating them back to Persians); thus the Exotic Shorthair was born. After much work by these dedicated UK breeders, preliminary GCCF recognition was granted to Exotics in 1986, followed in 1995 by full Championship status. Since then Exotics have become very popular and are always amongst the top show winners in the UK." Until 2000, the GCCF allowed outcrossing to British Shorthairs. The British Shorthair was dropped as an allowable outcross for Exotics in 2000. Exotics and Persians may be bred together.

Some Exotic Shorthairs carry the recessive longhair gene from their Persian heritage. When two carriers are bred together, longhaired offspring can appear. Most registries allow these to be registered as Persians or Persian Variants, although the coat quality is usually less long and full than that of a Persian. The CFA registered them as Exotic Longhairs based on their shorthaired parentage. In Australia, the longhaired progeny of Exotic Shorthairs may be registered as Persian Variants. The Exotic Shorthair also has a wider range of colours because of the Burmese and Siamese in its background which produce colourpoint, mink and sepia patterns.